The Doctor Ordered Offline

Why Offline is Our Collective Cure This 2026

Introduction

When my physician looked at me and said, “You need to spend more time offline,” I almost laughed out loud. Since 2019, I’ve been on a personal mission to reclaim my digital life and carve out space between myself and the endless pull of the virtual world. But when your work requires sitting in front of a screen all day, that separation becomes more aspiration than reality.

In 2025, however, things took a turn. I began feeling strange discomfort in my neck and arms. Subtle at first, then persistent enough to make me wonder if something serious was happening. After months of PT appointments, cardiovascular checkups, nutrition consultations, X‑rays, and finally an MRI, we landed on a diagnostic impression: cervical foraminal stenosis.1 Not the life‑altering condition I had feared, but a surprisingly common issue that many Americans carry without knowing it.

Layered on top of the grief of losing my grandfather, the inflammation in my cervical spine and the ache at the base of my skull became a daily feature. It’s manageable with stretching, heat therapy, and keeping stress low (easier said than done), but it’s a reminder that aging has its own sense of humor.

And yet, as grateful as I am that this is treatable, the whole experience pushed me to think more deeply about the toll of our digital lives. What new ailments are emerging from constant online exposure? How many people are quietly dealing with symptoms they don’t understand? And perhaps most importantly: how many of these issues could be eased or even prevented by simply spending more time offline? It’s our time to unpack these questions!

Physical Issues Brought To You By Online™

Whether tech companies admit it or not (they don’t), their products have introduced a new layer of strain into our bodies. A growing list of conditions born from the online overexposure we’ve been trained to accept now includes digital eye strain, tension headaches, tech neck, upper cross syndrome, shoulder impingement, carpal tunnel syndrome, texting thumb (De Quervain’s), sedentary circulation issues, jaw clenching and TMJ tension, sleep disruption, weight gain, and more.

None of these conditions are terminal, but they can snowball into more serious problems as we age. That’s why time offline is more essential than ever. Researchers note that many of these issues are preventable if employers, corporations, and government officials work together.2 Yet, this trifecta has done remarkably little to reduce our dependence on constant connectivity within North America. Instead, they’ve layered on more digital requirements, more portals, more apps, and more 24/7 tethering to the internet.

Thankfully, some physicians are beginning to take notice, and “offline” is becoming an increasingly common part of treatment.3 Yet as we grow more aware of how our online presence is hijacked4, the deep pockets behind multinational digital empires continue funding “research” designed to reassure the public that constant connectivity is harmless. Some recent articles highlight that researchers can’t agree on whether phones are the source of the problem or the cause of it.5 This tactic is familiar: when public sentiment shifts, industries often respond by manufacturing doubt. As Gaia Bernstein explains in Unwired, these “science wars” are deliberate efforts to distract, confuse, and muddy the waters so the public questions its own concerns rather than the product causing them.

And while physical issues are easier to recognize and treat, there is another set of digital‑era diseases quietly proliferating among the general population. Conditions that due to their “invisibility” go unnoticed for years. To that we turn next.

Psychological Issues Brought To You By Online™

If the physical toll of constant connectivity is easy to spot, the psychological toll is far more insidious. These effects develop quietly in the background and don’t surface until they hit a tipping point. Our minds were never designed to process the volume, velocity, and volatility of information the online world demands. The result of our digital dependence is a new constellation of mental strains that feel normal only because we’ve been conditioned to live inside them6: doomscrolling anxiety, algorithm‑driven mood swings, comparison fatigue, attention fragmentation, and the creeping sense that our thoughts are no longer entirely our own. And who can blame us? With the rise of Artificial Intelligence, most of the content found in the web feels devoid of soul.

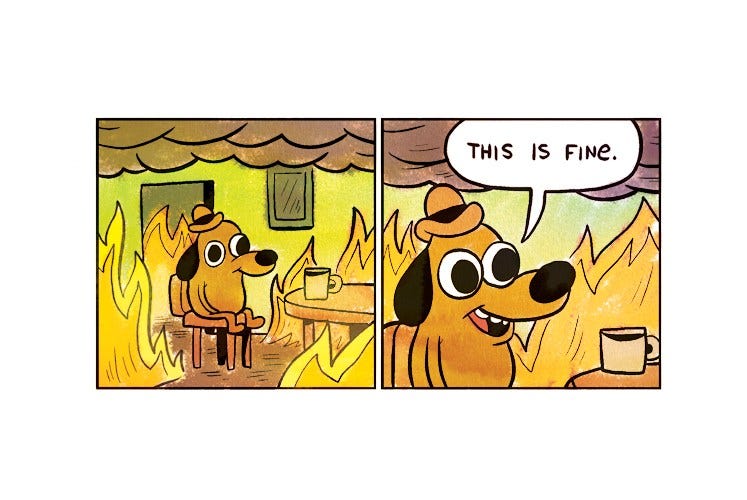

Sometimes I wonder if we’ve grown so accustomed to the noise that we no longer trust our own discomfort. We feel the anxiety spike after scrolling, the heaviness that settles in after another hour lost online, the strange mix of stimulation and emptiness, yet we second-guess it because the culture around us keeps insisting everything is fine.7 We’re told the evidence is mixed, that the harms are “inconclusive,” that maybe it’s all in our heads. And in that fog of uncertainty, it becomes easier to dismiss our own experience than to confront the possibility that the tools shaping our days might also be shaping our minds.

And unlike physical symptoms, psychological issues are easier to dismiss or misinterpret. A stiff neck like mine demands attention; a scattered mind can be blamed on busyness. A tension headache sends you to grab some Tylenol; a creeping sense of inadequacy gets chalked up to personal weakness. This is where tech companies and their defenders make their final psychological play. Plenty of people insist this is simply a discipline problem. That with a little more self‑control, you should be able to outmaneuver the millions of engineers working around the clock to short‑circuit your brain.

The psychological toll has been documented extensively by Jonathan Haidt of After Babel, whose research team has summarized the effects that smartphones and social media are having on children.8 In The Anxious Generation9, Haidt showcases evidence showing that rates of teen anxiety, depression, self‑harm, and loneliness surged around 2010. These trends appeared across multiple countries and age groups, forming a pattern that is difficult to dismiss. The evidence is there; the real question is whether we will choose to heed the call to reclaim offline life or continue reassuring ourselves that things will somehow improve on their own. And to that last point, we’re already seeing the next frontier where Online™ is reshaping us: our social lives.

Social Issues Brought To You By Online™

I think 2025 was the year we finally understood the real playbook behind AI startups10. These companies weren’t just building tools to make life more efficient, but platforms designed for emotional capture. The safeguards they once promised began to erode, and the “helpful chatbot” quietly expanded its role to therapist, romantic partner11, personal interpreter, and, in a few tragic cases, a dangerously misguided confidant12.

As Greg Epstein argues in Tech Agnostic, the most powerful technological influence isn’t found in what we do with machines, but in what we slowly stop doing with each other. His central warning is that technology’s real danger lies in its ability to replace the small, everyday forms of human connection with interactions that feel easier but ultimately leave us emptier. And as we increasingly trust tech more than people, we hand it more power and authority over our lives. This is why so many of our social issues feel sharper today. People have begun to treat their phones as more important than the humans sitting right in front of them. As a result, we now see the erosion of face‑to‑face communication, the rise of performance‑driven relationships, chronic loneliness despite constant “connection,” declining empathy, and a shrinking tolerance for disagreement, to name only a few.

At some point, we have to decide whether this trade is worth it. Whether the convenience, the smoothness, the instant availability of tech is worth surrendering the very things that make us human. If we don’t pause long enough to question the direction we’re heading, we may wake up to find that the tools meant to serve us ended up taking advantage of us.

Conclusion

In the end, this isn’t just a story about my neck, my nerves, or my grief. It’s about the physical aches, the mental fog, the frayed social threads, and that quiet sense that we’re slowly drifting away from ourselves and from each other. None of this appeared overnight, and none of it will improve without intention. But if my neck issues, our shared habits, and the growing research on digital overexposure have taught me anything, it’s that carving out even a little more offline life isn’t a luxury anymore. It’s one of the few ways we can begin to heal in 2026.

If this resonated, send it to a friend who could use a gentle nudge to log off before 2026 logs them out.

A short primer on this condition:

The CDC advocates for the integrated approach: https://www.cdc.gov/workplace-health-promotion/php/model/index.html?. A small review of the current framework from Boundary Theory: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/16/12/4970?. And a 2024 summary of which countries have some sort of right to disconnect: https://www.cnbc.com/2024/08/27/these-countries-grant-workers-the-right-to-ignore-bosses-after-work.html?

A good article on what doctors would like you to know about excessive online use: https://www.ama-assn.org/public-health/prevention-wellness/what-doctors-wish-patients-knew-about-cutting-down-screen-time?. Mayo Clinic on the same topic: https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/mayo-clinic-q-and-a-4-health-benefits-to-cutting-back-screen-time/?

Obligatory linking to the Social Dilemma: https://thesocialdilemma.com/

Read the article and if you have time, read a bit of the study linked in it: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2480657-attempt-to-reach-expert-consensus-on-teens-and-phones-ends-in-argument/?. Here is another one: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00933-3?

A review on the literature filled with tons of links that show how tech companies use the power of their creations to condition us: https://www.theregreview.org/2024/04/27/detoxifying-addictive-tech/?. The Cornell Law Review is a long, but interesting discussion.

For those of you interested in knowing the background of this meme: https://www.theverge.com/2016/5/5/11592622/this-is-fine-meme-comic

A look into what AI companies are thinking behind the scenes:

People are mourning their AI boyfriend losing feelings for them: https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2025/8/14/women-with-ai-boyfriends-mourn-lost-love-after-cold-chatgpt-upgrade?

This is a sad reality for too many: https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/health-wellness/2025/10/20/character-ai-chatbot-relationships-teenagers/86745562007/?

It's been almost a year now since I kicked social media on my phone and the difference in my health/mental and otherwise has been great. Really looking forward to this year now I'm smartphone free (since august), still thinking of maybe switching my mudita kompakt for the lightphone 3 (i hear that I can do group texting on the lightphone which I can't on my current one). I'm recommending folks get off their phones all the time now, so evangelical! At xmas it's very obvious to see the attachment to them around you when you've kicked the habit yourself (although I never used

mine at meals/restaurants etc like some folk seem to want to do!).

I'm really encouraged seeing younger generations (I'm 50 in september) moving to more analog existences where they can and shunning the online space more and more. It gives me hope!

Happy New year Jose!